Farming the Data: The Critical Need for Tech and Data Literacy in Food and Agriculture

Editor’s note: Joyce Hunter is the Executive Director of the Institute for Critical Infrastructure Technology (ICIT) and the Distinguished Fellow for Food, Agriculture and Healthcare. She is also an Ambassador for the Women in Ag Tech initiative and was a recent guest on the Global Ag Tech Initiative’s Ground Breaking Podcast. In this article, Joyce shares insight into the importance of investing in education, training, and infrastructure to support tech and data literacy so we can unlock the full potential of data-driven solutions for a more resilient and productive food system.

Our fast-paced, ever-evolving world often tricks most into believing that technological interconnectivity is the backbone that frames and supports daily life. While digitization, modernization, and security of our critical infrastructures are vital for innovation, accessibility, and progress, they remain operations that augment the underlying sectors: networks of people, processes, and technologies. Humanity evolved, established connections, formed communities, developed societies, built nations, and advanced technology to acquire, generate, or utilize agricultural products.

Nations differ in how they define, classify, and prioritize critical infrastructures due to factors such as culture, technology, resources, agendas, etc. Every nation considers food and agriculture to be of the utmost necessity. The need to eat is a universal trait that transcends ideological barriers, topographic boundaries, and geopolitical borders. To offset significant challenges such as the effects of climate change and continue to meet ever-increasing global demand, food and agriculture stakeholders ranging from international mega-corporations to small family farms are integrating emerging technologies into every facet of their second-to-second operations. Incorporating IoT (Internet of Things), machine learning, and other technologies reduces costs, minimizes waste, and mitigates some threats; however, they may also introduce catastrophic risks when not deployed with security in mind.

Long ago, at the advent of human conflict, one of the first, most brutal, and most effective tactics that colonizers and conquerors learned was that entire populations and civilizations could be manipulated or eliminated through even brief food and agriculture sector disruptions. Adversaries, including meddling script-kiddies, radicalized hacktivists, opportunistic cybercriminals, callous cyber-terrorists, and sophisticated nation-state sponsored advanced persistent threat actors (APTs), will find value in compromising under-secured food and agriculture systems. Investing in cybersecurity is essential for small and medium-sized farmers to protect their data, financial assets, supply chain integrity, reputation, and intellectual property. By implementing robust cybersecurity measures, farmers can mitigate risks, ensure regulatory compliance, and maintain trust and confidence among stakeholders in the supply chain.

Another Day on the Farm

Farmers are perceived as hands-in-the-dirt, work-from-dawn-to-dusk, physical laborers, but they are, and have always been, data scientists. Even in the antiquated past, farmers could estimate crop yield from previous years and the current characteristics of their plants, predict livestock development based on behavior and growth, and optimize resource application across a dynamically changing environment to maximize positive outcomes and minimize future risk. In 1818, the “Farmers’ Almanac” was named for and marketed on the societal assumption that farmers understood data enough to forecast weather, predict market outcomes, or better understand the natural world enough to guide the philosophical and esoteric topics contemporaneous to the era. Modern farmers are no less immersed in data analysis than their predecessors. In fact, in nearly every instance, successfully operating a modern farm or agricultural business necessitates fostering technological developments as much as it does to raise livestock or a field of crops.

The modern farmer is a jack-of-all-trades. To successfully generate a profit and produce enough output to meet market demands, farmers must be experts in soil nutrition, fertilizer and insecticide impacts, plant lifecycles, irrigation methodologies, weather patterns and climate impacts, supply chain logistics, labor management, resource allocation optimization, livestock behavioral patterns, equipment maintenance, and numerous other operational intricacies. Now, they must also be fluent in computer science, data analytics, robotics, machine learning, and other evolving fields.

Groundbreaking Podcast: How Public and Private Sectors Can Work Together to Reduce the FUD Factor

There are already hundreds of “AI-based” agricultural startups and solutions vendors; however, given how slim agricultural profit margins already may be, the adoption of many vendor solutions could prove devastating if the products do not deliver on their promises or if the associated risks and limitations are not fully understood. Global survival depends on farmers developing enough technological and data literacy to conduct needs and risk assessments, evaluate the reality and viability of solutions, understand and strategically act on algorithmically derived insights, and tailor systems and solutions to their operational needs.

Only Farmers Can Address Global Food Insecurity

Aside from oxygen and water, food is every human’s most immediate and vital need. Much like an engine requires an input energy source to operate, farmers produce the resources that drive our people, processes, technologies, and society forward. The yield and quality of their crops, products, and byproducts directly determine the effectiveness and health of our workforce, economies, and critical infrastructures. Without accessible and consistent sustenance that meets or exceeds our nutritional needs, we live shorter and more insular lives, are less creative, efficient, and productive in our activities, and are severely limited in our abilities to address personal, societal, and global challenges.

Food insecurity is defined by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) as irregular or insufficient access to safe and nutritious food sufficient for normal growth and development and an active and healthy life. The FAO measures and categorizes food insecurity as mild, moderate, and severe. Food insecurity is the culmination of various issues, including high inflation rates, weather shocks, volatile fertilizer markets, reduced crop yield, increased urbanization, geopolitical conflicts, and other factors. The USDA estimates that in 2022 approximately 12.8% of all U.S. households – and 17.3% of households with children – experienced at least mild food insecurity in 2022. According to the 2023 State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World report, 691-783 million faced hunger in 2022 (~9% of the global population), an additional 2.4 billion people experienced moderate or severe food insecurity (~30% of the global population), and 900 million faced severe food insecurity (~11% of the global population). Over 3.1 billion people could not afford a healthy diet (~39% of the global population). Approximately 30% of rural adults experienced moderate or severe food insecurity in 2022, compared to 28.8% in peri-urban and 26% in urban areas. Nearly 600 million are projected to be chronically undernourished by 2030.

The United Nations estimates that the current global population of 7.6 billion will increase to 8.6 billion by 2030 and 9.8 billion by 2050. The respective 13% and 29% increases in the current global population will proportionally increase demand for food and agricultural products while potentially decreasing the availability of arable land. In every nation, vital supply chains, critical infrastructures, and the workforce’s health and productivity may experience noticeable strain and impacts if proactive steps are not taken now to mitigate future scarcities.

Agricultural production can only be increased by expanding land use or leveraging emerging technologies to maximize productivity, crop yield, and growth cycles. Available arable land is already a limited and sometimes contested resource. It may be further reduced by the impacts of climate change, diminishing soil fertility, or the competing interests of energy companies, commercial property, and other sectors. Farmers must also contend with intellectual property licensing and disputes, an increasingly disinterested and diminishing emerging workforce, and numerous other market barriers and economic disincentives that threaten even the most meager profit margins. Automation, emerging technologies, and the precise and strategic application of resources according to real-time, data-driven models are the only practical solutions to every farmer’s current and future challenges. Fortunately, every season brings a new and diverse crop of technologies and solutions that farmers can experiment with to try and best address their business needs.

Food and Agriculture is Already at the Technological Forefront

Since the very first crop and tool, farmers have been the pioneers of harvesting insights from data and shepherding nascent technologies. However, while humans are impressive machines, our observational capabilities and intuition have upper bounds that are far exceeded by the tools and technologies we can deploy. Data’s value and utility derive from how it is processed, combined, interpreted, and implemented.

Modern agribusinesses leverage sensors, data analysis models, autonomous units, and other advanced tools to collect and analyze data, measure soil characteristics, monitor their supply chain, track weather patterns, mitigate threats to their crops, determine optimal sowing and harvesting windows, forecast yields, evaluate fertilizer and pesticide impacts, anticipate market trends, and otherwise boost the productivity and profitability. Every sector, industry, and aspect of life is currently fixated on the promises of artificial intelligence, and the food and agriculture sector is no exception. Strategic automation solutions like driverless tractors, smart irrigation, fertilization systems, IoT-powered agricultural drones, smart spraying, vertical farming software, and AI-based weeding and harvesting drones may help mitigate labor shortages, maximize land utilization, and reduce waste.

Meanwhile, robust machine learning solutions, vertical agriculture, and precision agriculture can empower farmers to make data-driven, near-real-time decisions that maximize yields and minimize costs. These solutions can help ensure and improve soil nutrition, detect and repair equipment damage, generate crop insights, optimize the rate of growth and food production, detect and eliminate disease and pests, monitor and address livestock health, map yields and conduct predictive analytics, sort harvested produce, and otherwise optimize operations.

For example, the UN estimates that 17% of total global food production is wasted, and that loss also accounts for 38% of the total energy usage of the global food system. Estimates are not readily available to tabulate the water, land, labor, capital, disposal, emissions, and other losses correlated with the cumulative waste. While machine learning and emerging technologies will not entirely eliminate food system waste, every percent of global food production that can be rendered edible by taking proactive steps during the production process will actively save millions of lives, increase profits, and decrease consumer costs.

We Need Farmers to be Data-Literate and Technologically-Proactive

Humanity’s current and future survival depends on farmers incorporating knowledge from even more fields into their discipline, taking risks on emerging technologies, and expending the resources necessary to modernize the backbone that supports every aspect of society.

By deploying real-time sensors, collecting and tracking meaningful data, supplementing labor with automation, and acting on actionable analyses, farmers can increase profits, improve operational efficiency, minimize waste, reduce food scarcity, and save lives. We are asking farmers to assume significant risk and invest their already strained time, resources, and trust in data-driven solutions that can help them “save the farm.” Less metaphorically, we are tasking them with saving humanity.

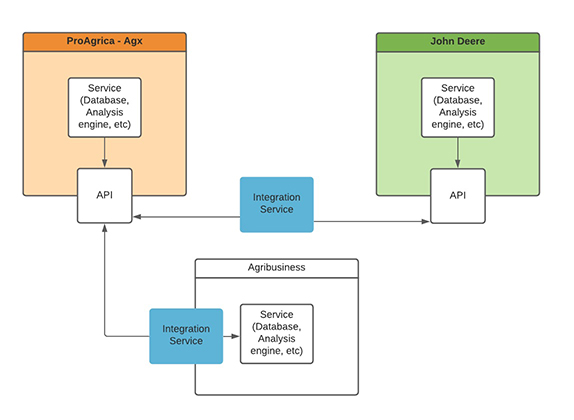

Better-resourced supply chain partners that commercialize agricultural products could ensure a future of more consistent and robust produce, livestock, and other goods in exchange for helping the farms in their supply chain modernize and better acclimate to the data-driven present. Consumers also should care about the security and resilience of the food and agricultural sector because it directly impacts their health, safety, access to food, economic well-being, and the sustainability of the environment. Protecting this domain from cyber-attacks, natural disasters, bioterrorism, or other threats is essential to maintaining food security and national sovereignty. Even just understanding the importance of this infrastructure and supporting measures to strengthen its resilience and security, consumers can contribute to a more sustainable, secure, and resilient food system.

Significant public-private sector collaboration will be needed to develop the training and frameworks necessary to modernize the food and agriculture sector. As much we are demanding of farmers, it behooves local, state, and federal policymakers to take the time to understand the sector’s data literacy and technology needs and to responsibly and immediately allocate the resources necessary to ensure that our current and future agricultural needs can be met.

Conclusion

From farmers to policymakers, understanding and harnessing the power of data-driven technologies can drive innovation, improve efficiency, and ensure sustainability in food production. By investing in education, training, and infrastructure to support tech and data literacy, we can empower individuals and organizations to navigate the complexities of modern agriculture and unlock the full potential of data-driven solutions for a more resilient and productive food system.